It was pure chance which first led me to the MSSP Oratory in Birkirkara. On a particularly dark and dreary afternoon, after having procrastinated all day, I decided to go to Mass at the oratory. Alas, my choice was initially purely utilitarian: Mass was at a convenient time, it was a relatively short drive home and there was parking next door to the church.

As I entered the oratory, I was immediately struck by the atmosphere. Before Mass, there was a reverential silence. The warm dim light made the icons stand out in the semi-darkness.

During Mass, a carefully crafted liturgy drew on the significance of gestures and pauses, and the link between Word and Sacrament. After Mass, people spoke to one another. This was not just a congregation but a community of believers.

It is difficult to put into words what liturgy, community and fellowship mean; one must experience this first-hand to appreciate why it is necessary.

The Missionary Society of St Paul (MSSP) has been present at the oratory since 1927. This society needs no introduction in Malta. Founded by Mgr Giuseppe de Piro, it is now present in many countries around the globe, offering material assistance and spiritual comfort in the most peripheral locations.

The mission of the MSSP Oratory in Birkirkara is inspired by the desire to offer meaningful liturgies in beautiful surroundings. This is not a matter of mere aesthetics; in the tradition of the Church, the Via Pulchritudinis – the path of beauty – is a long and time-honoured way of evangelising for in the beauty of our surroundings we can see glimpses of the beauty of God.

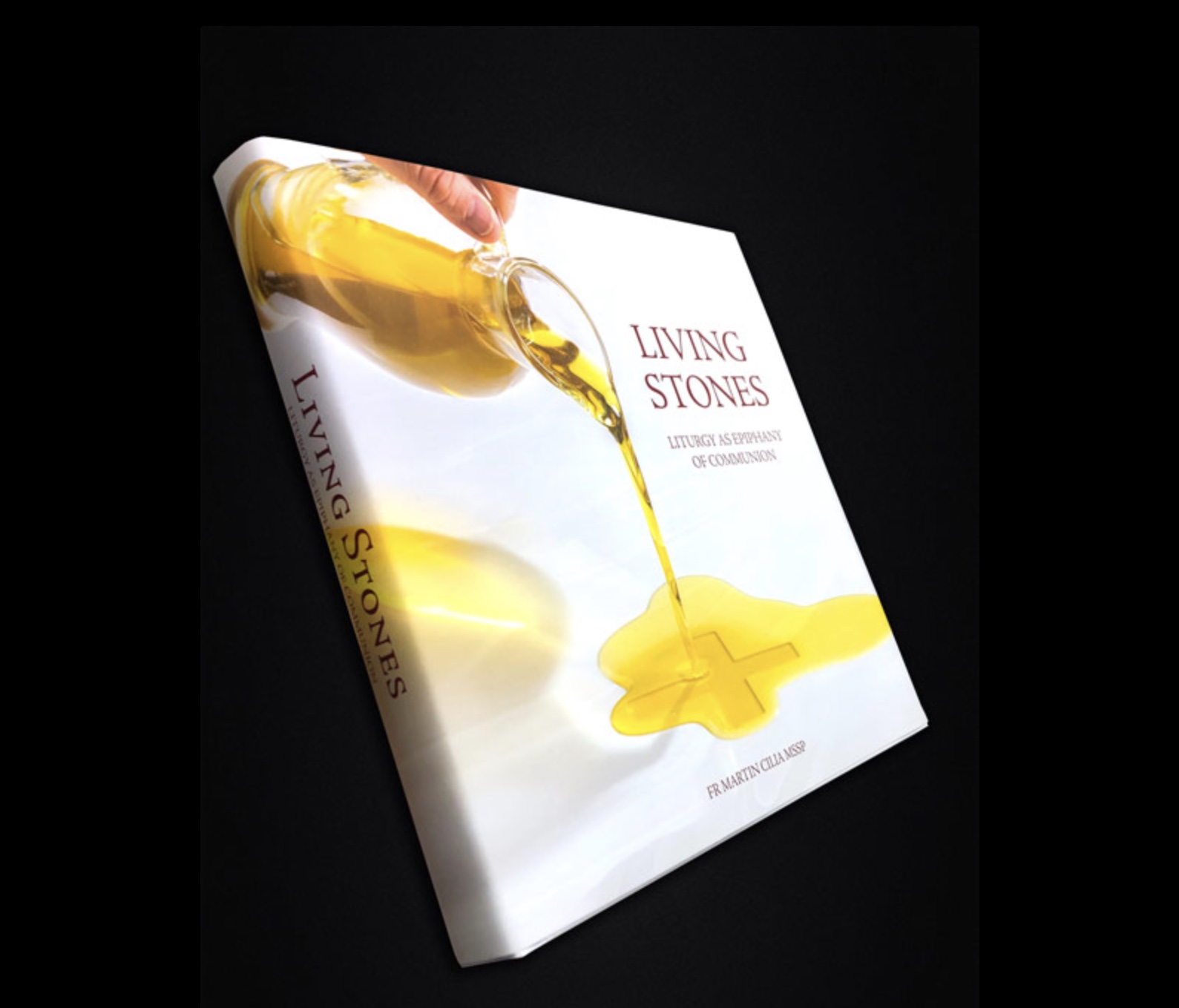

In the recently-published book Living Stones, the director of the MSSP Oratory Fr Martin Cilia remarks on the link between mission and beauty: “Missionaries understand their ministry as that of preparing the way for an encounter with Christ to take place. Beauty helps people to fall in love, and love reveals the substance and identity of God.”

In the last decade or so, the oratory has gone through a complete redesign, not only to accommodate new pastoral realities but also to reflect our journey of faith. This journey of faith involves the entire community and is centred on the mystery of Easter.

Beauty helps people to fall in love, and love reveals the substance and identity of God

In this richly -illustrated volume interspersed with quotes from the Fathers of the Church and liturgical texts, Fr Martin gives the reader a glimpse of how this journey unfolds at the oratory. It brings to life the experience of the priests living in this community and the hundreds who worship there every week.

One enters the church through a glass door portraying the image of the Mother of God. A golden line on the floor leads to the baptismal font. This serves as a permanent reminder of the sacrament of baptism or “the doorway of all the sacramental life of the church”.

The church is adorned with beautiful icons written by Nathaniel Theuma. They depict the Baptism of Christ, the Annunciation, the Nativity, the Resurrection, the Deposition and the Transfiguration. In the centre of the church, above the Tabernacle, is the icon of Christ Pantocrator (the all-seer) – an image popular in Eastern Christianity which shows Christ holding an open Gospel.

These icons are not merely there to decorate bare walls; instead, they were commissioned “so that the very walls would proclaim the Christian mystery.” Each icon “is a spiritual work of art through which the artist uses colour to proclaim the Good News of the Gospel, thus helping people pray in beautiful and meaningful surroundings”.

That same Gospel is also proclaimed and explained on the ambo. Within the ambo, a recess allows for an additional icon to be displayed – often marking a particular saint of depicting a scene from the Gospel readings.A strong link is forged between the ambo and the icons. They serve to unite the Western and the Eastern traditions of the Church: “While Western spirituality emphasises listening, because faith comes from listening, Eastern spirituality regards gazing as a vehicle for faith.”

The heart of the liturgical space is the altar which serves as a “permanent sign of the Risen Christ among his people”. The design of the altar is simple in order not to detract any attention from the offering of the Mass. It is made of the same material used for the baptismal font, the ambo and the chair of the celebrant – thus emphasising the unity between each.

In creating this space laden with symbolism and meaning, there is much to be applied in a broader context to the journey of faith.

Firstly, the church is not merely about buildings. It is primarily about a community of people who gather together and seek to grow together in faith. This is consistent with the original meaning of the Greek word ecclesia, which stands for an “assembly of people”.

Secondly, though not primarily about buildings, the Church meets in specific spaces for worship and fellowship. These need to be beautiful and welcoming places reflecting the message being proclaimed. As Pope Benedict XVI rightly observed, “the purpose of sacred architecture of today is to offer the church a fitting space for the celebration of the mysteries of faith”.

Thirdly, that same Church must be nourished by the Word of God and the tradition of the Church – both Western and Eastern. These traditions have always valued the Way of Beauty – be it through the poetry of the liturgies, the transcendent quality of its art, the enduring symbolism, the writings of the Fathers of the Church and the monastic and conventual legacies.

As this marvellous new book reminds us, it is thus essential that “the meeting place becomes the ‘physical reminder’ of the real journey, that is, the interior journey”.

The article first appeared in Times of Malta on 3rd October 2020.